To put out the fire, Malibu wants to arrest homeless people who refuse to stop camping illegally

[ad_1]

On Monday morning, a homeless man sat in front of the Malibu County courthouse, where he sleeps every night.

In front of him was a small, green tank with a flashlight attached, which he said he uses for cooking and making wooden pipes with tobacco and cannabis.

A short walk away is Legacy Park, the Oasis of Frairies Coastal Cariaries, Bluffs and Women’s Areas. The Santa Monica Mountains rose in the background.

“Sometimes, someone will see one of us cooking and they’ll call the…

In Malibu, hard-hit by the Palisades fire and prone to long-term droughts, elected officials and some residents cower in fear or use flames to stay warm in the air.

Last month, to deal with the high fire risk, the Malibu city council declared a state of emergency and directed the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office to remove people involved in the empty camp and, if necessary, arrest them.

“Malibu’s history as it relates to the most devastating fire,” said Mayor Marianne Riggins in an interview. “We are making every effort to minimize the possibility of that type of destruction.”

City staff initially proposed directing Sheriff’s officials to ensure the city was not aggressive, while also confirming that those efforts were not ‘planned for the living.’

At the request of Councilman Bruce Silverstein, that language was removed and the arrest language was added.

The officials who will answer will answer vaguely. At the meeting, the Captain said that the police were limited in what they could do, because it was the city’s policy not to be at home.

Silverstein argued that since Malibu is an incorporated city that contracts with the Sheriff for law enforcement services, officers should follow Malibu policy, not the County. He pointed to Supreme Court grants that came last year that overturned previous backlogs and allowed cities to enforce anti-tent ordinances.

The Sheriff’s Office did not respond to a request for comment.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath, whose district includes Malibu, said that “Residents are not happy, but they look at” Malibu’s residents’ deepest goals for keeping our fire-prone communities safe. “

In a statement, Horvath said that last week his office worked with the city of Malibu, the Sheriff’s department and homeless service providers to leverage capital and improve their presence and resources throughout the Santa Monica Mountains. “

Malibu residents and officials say they have reason to be more aggressive.

Last week, the authorities arrested an Uber driver, they said they started a fire on purpose, which revived and four in Malibu, and destroyed four in Malibu, and destroyed four in Malisal City and thousands of people in the sea.

What we use. Bill Essayli speaks as Los Angeles Police Chief, right, at a news conference announcing the arrest of Jonathan Rinderkenit, on Oct. 8 in Los Angeles.

(Christina House/Los Angeles Times)

In court documents, authorities said the man was homeless. But as of 2021, the city said there were more than 30 fires believed to have been started by homeless people.

The City’s Director of Public Safety, Susan Rudñas, told The Times that she was not aware of any major damage from the camp fire.

But that may not be true in the future.

“Any one of those would have been a double whammy,” Silverstein said in an interview.

A few weeks before the destruction of January, the Franklin fire ripped through the hills above the County courthouse in Malibu and destroyed 20 structures and damaged another California department of forestry and fire protection. The cause is still under investigation, the agency said.

One of the most recent fires from unoccupied tents was on Sept. 24, on vacant land near the Malibu Racquet Club, according to the city.

In an online post, the city described it as a “small cooking fire” that was quickly put out by firefighters, while a homeless person was camping on the spot.

Michelle Jackson, 58, gave up her home on the hill above that fire.

The private chef said he supports enforcing the law if people don’t stop illegal camping, noting that when Santa Ana pulls the whip with Malibu “it doesn’t really catch fire.

“We all work hard and pay our bills to live here,” Jackson said. “I wish we had a better solution to homelessness, but it doesn’t mean I want it in our backyard.”

Richard Garvey, who has lived in Malibu for more than 40 years and is the head of a successful volunteer drug response program, said he is concerned the campfires are widespread and held by Malibu residents who have different views on providing for vulnerable people.

He said local residents have encouraged in their backyards, but that is in a contained area with easy access to water if something goes wrong.

“People who come out of this area don’t see the unique dangers that present themselves to us,” Garlovey said.

As a result, Malibu’s director of public safety, said some homeless people in Malibu are from the city, but most are from elsewhere.

He said the city has had success housing people in recent years and has reduced the number of homeless people from 150 in 2021 to 30 to 30 to 40 on a given day.

Cadualo said most of the homeless people live in the community center area, where the County Courthouse, Library and Legacy Park are located. If people are living in the brush, then the city is working quickly to move them somewhere else.

Daniel, a homeless man outside the county courthouse, said he is from Michigan but has been homeless in Malibu, Topanga and Santa Monica for 21 years. He said he thinks the fear of the homeless will cause large fires to spread and he said he cooks with propane, not wood, which can easily spread bembers.

When the fire department was called to him, Daniel said he had also been pouring concrete in front of the County Courthouse, removed from the brush of Legacy Park.

Not everyone seems to do that.

Last month, a local resident sent a video to Operator of a Skillet filled to the top of a high-rise fire pit in the brush at Legacy Park. Next to the pit, where at least some plants were used as fuel, were mattresses, a shopping cart and a tarp.

Cadualo said that while the Council is directing more aggressive action, the city is trying to balance fire protection and public safety with compassion for the homeless and “remains committed to communicating with our outreach teams.”

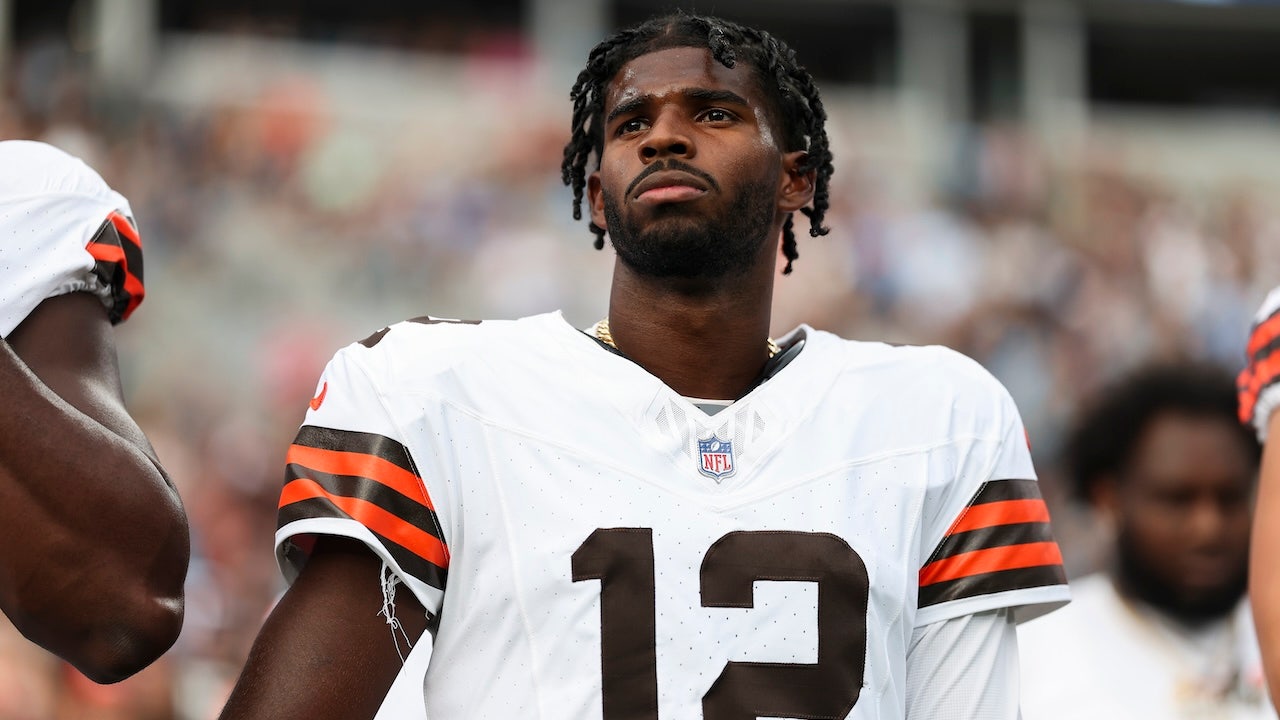

David Verwey, 37, watches a man walk his dog in the heart of Legacy Park, where he has been living for the past two months in Malibu on Oct. 15.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

On Monday morning, David Verwey rested on a bench inside the estate, where he spent the night.

Originally from Michigan, Verwey said he moved to California a few months ago, due to a toxic situation with an ex. Now homeless, the 37-year-old former factory worker spends his nights in the Zuma park or beach.

Unlike other people, he said he does not use fire to cook or to avoid heat and he understands the residents’ concern that such work can start a blaze and “it is something that needs to be taken care of.” He said the Malibu community has supported him and other homeless people, offering free meals several days a week.

Vewey said he hopes to one day find work in the entertainment industry. For now, he is sleeping in Malibu because he feels safe and peaceful.

As he sat on the bench with his bag by his side, Verwey looked at the marshes and the mountains rising across the water.

“I’m completely satisfied with being homeless here,” she said. “This is God’s country.”